Problem: Given a set $S$ of $N$ points in the plane, for each point $p_i$ in $S$ what is the locus of points $(x,y)$ in the plane that are close to $p_i$ than to any other point $S$ ?

Definition locus is the set of points whose location satisfies by one or more specified conditions.

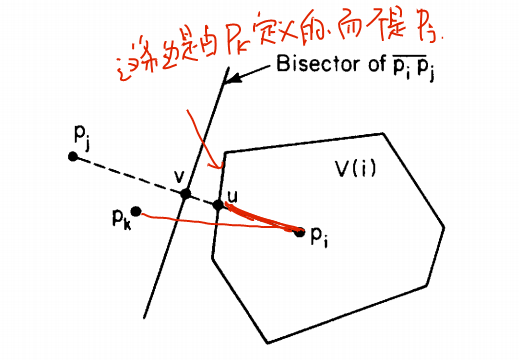

Given two points, $p_i$ and $p_j$, the set of points closer to $p_i$ than to $p_j$ is just the half-plane containing $p_i$ that is defined by the perpendicular bisector of $\overline{p_ip_j}$. Denote the halfplane by $H(p_i,p_j)$. The locus of points closer to $p_i$ than to any other point, which we denote by $V(i)$, is the intersection of $N-1$ half-planes, and is a convex polygonal region having no more than $N-1$ sides, that is:

\[ V(i)=\cap_{i\neq j}H(p_i,p_j) \]

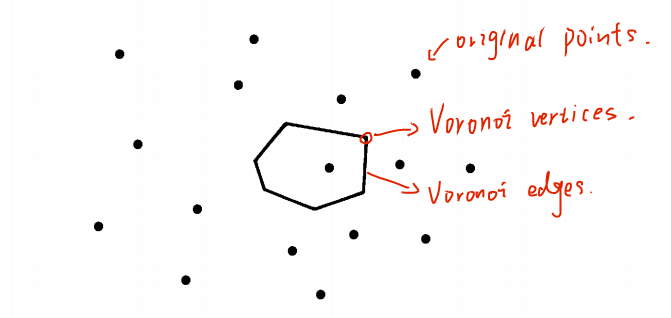

$V(i)$ is called the Voronoi polygon associated with $p_i$.

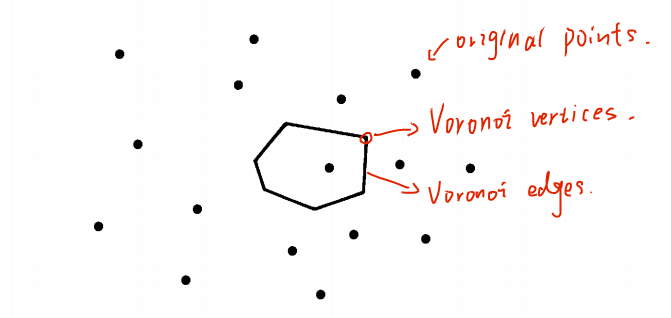

These $N$ regions partition the plane into a convex net which we shall refer to as the Voronoi diagram, denoted as $Vor(S)$. The vertices of the diagram are Voronoi vertices, and its line segment are Voronoi edges. Each of the original $N$ points belongs to a unique Voronoi polygon; thus if $(x,y)\in V(i)$, then $p_i$ is a nearest neighbor of $(x,y)$. The Voronoi diagram contains, in a powerful sense, all of the proximity information defined by the given set.

A catalog of Voronoi properties

Assumption No four points of the original set $S$ are cocircular.

Theorem 5.7 Every vertex of the Voronoi diagram is the common intersection of exactly three edges of the diagram. The equivalent form is, the Voronoi vertices are the centres of circles $C(v)$ defined by three points of the original set, and the Voronoi diagram is regular of degree three.

A graph is regular if all vertices have the same degree.

Proof

- Let $e_1,\cdots,e_k$ be edges incident on Voronoi vertex $v$. Note that $x$ is equidistant from $p_{i-1}, p_i$ since it belongs to $e_i$, thus, $v$ is equidistant from $p_1,p_2,\cdots,p_k$. But this means that $p_1,\cdots,p_k$ are cocircular, violating assumption that $k\leq 4$.

- If $k\leq 3$, say $k=2$, then $e_1$ is common to $V(2)$ and $V(1)$, and so is $e_2$: indeed they both belong to the perpendicular bisector of the segment $\overline{p_1p_2}$, so that they do not intersect $v$ (they are coincident).

Theorem 5.8 For every vertex $v$ of the Voronoi diagram of $S$, the circle $C(v)$ contains no other points of $S$.

Proof If $C(v)$ contains some other point, say $p_4$, then $p_4$ is closer to $v$ than to any of $p_1,p_2$ and $p_3$, in which case $v$ must lie in $V(4)$ and not in any of $V(1),V(2)$, or $V(3)$, by the definition of a Voronoi polygon.

Theorem 5.9 Every nearest neighbor of $p_i$ in $S$ defines an edge of the Voronoi polygon $V(i)$.

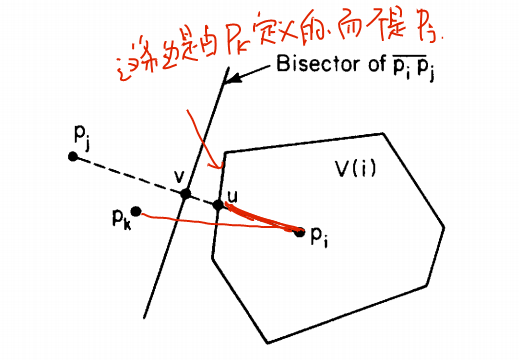

Proof Assume $p_j$ be a nearest neighbor of $p_i$ and let $v$ be the midpoint of their adjoining segment. Suppose that $v$ does not lie on the boundary of $V(i)$. Here we have $length(\overline{p_iu})<length(\overline{p_iv})$, so:

$$

length(\overline{p_ip_k})\leq 2length(\overline{p_iu})<2length(\overline{p_iv})=length(\overline{p_ip_j})

$$

and we could have $p_k$ closer to $p_i$ than $p_j$ is, which is contradictory.

Theorem 5.10 Polygon $V_i$ is unbounded if and only if $p_i$ is a point on the boundary of the convex hull of the set $S$.

Since only unbounded polygons can have rays as edges, the rays of the Voronoi diagram correspond to pairs of adjacent points of $S$ on the convex hull.

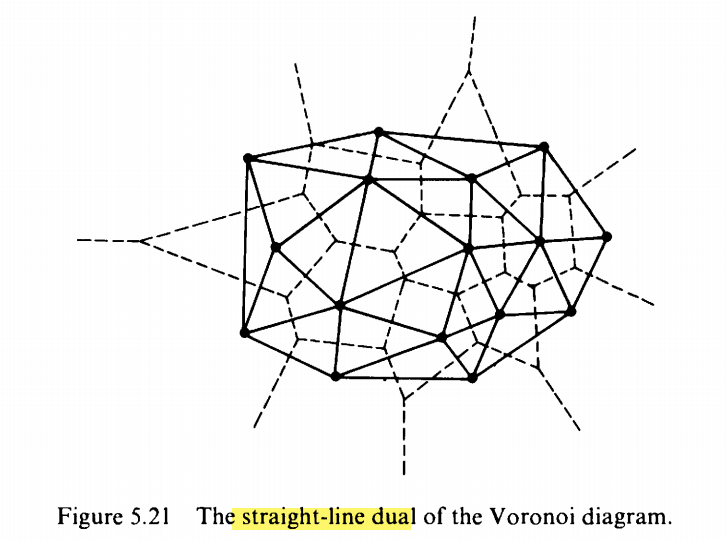

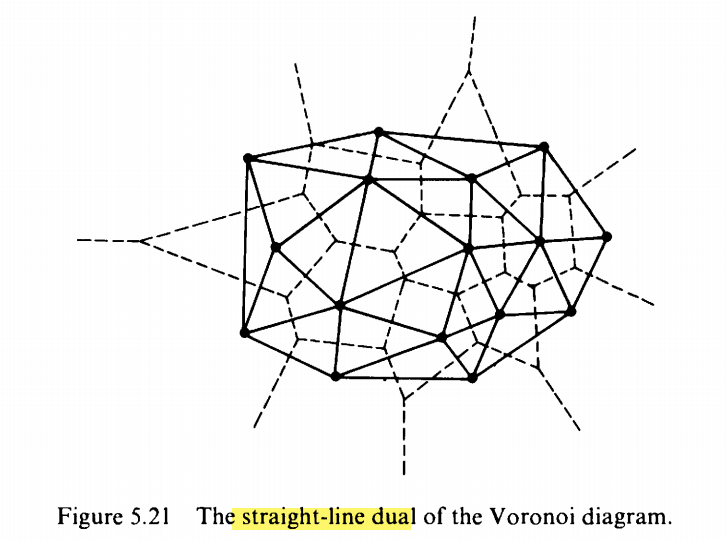

Theorem 5.11 The straight-line dual of the Voronoi diagram is a triangulation of $S$.

Euler's formula If $G(V,E)$ is planar on $n\geq 3$ vertices, then $\mid E\mid\leq 3n-6$ and $\mid f\mid\leq 2N-4$.

Below one less face is exempt from the outer most open one.

Corollary 5.2 A Voronoi diagram on $N$ points has at most $2N-5$ vertices and $3N-6$ edges.

Proof Each edge in the straight-line dual corresponds to a unique Voronoi edge. Being a triangulation, the dual is a planar graph on $N$ vertices, and thus by Euler’s formula it has at most $3N-6$ edges and $2N- 4$ faces. Therefore, the number of Voronoi edges is at most $3N- 6$; however, only the bounded faces (at most $2N - 5$) dualize to Voronoi vertices.

Any given Voronoi polygon may have as many as $N-1$ edges ($N$ points in total $N^2$ edges), but there are at most $3N-6$ edges overall, each of which is shared by exactly two polygons. This means that the average # of edges in a Voronoi polygon does not exceed $(2\times3N-6)/(N-1)=6$.

Constructing the Voronoi diagram

Theorem 5.12 Constructing a Voronoi diagram on $N$ points in the plane must take $\Omega(N\log N)$ operations, in the worst case, in the algebra computation-tree model.

Procedure VORONOI DIAGRAM (preliminary)

- Partition $S$ into two subsets $S_1$ and $S_2$ of approximately equal sizes.

- Construct $Vor(S_1)$ and $Vor(S_2)$ recursively.

- “Merge” $Vor(S_1)$ and $Vor(S_2)$ to obtain $Vor(S)$.

- Construct the polygon chain $\delta$, separating $S_1$ and $S_2$.

- Discard all edges of $Vor(S_2)$ that lie (extend) to the left of $\delta$ and all edges of $Vor(S_1)$ that lie to the right of $\delta$. The result is $Vor(S)$, the Voronoi diagram of the entire set.

What reason is there to believe that $Vor(S_1)$ and $Vor(S_2)$ bear any relation to $Vor(S)$ ?

Definition 5.2 Given a partition ${S_1,S_2}$ of $S$, let $\delta(S_1,S_2)$ denote the set of Voronoi edges that are shared by pairs of polygons $V(i)$ and $V(j)$ of $Vor(S)$, for $p_i\in S_1$ and $p_j\in S_2$.

This collection $\delta(S_1,S_2)$ of edges enjoys the following properties.

Theorem 5.13 $\delta(S_1,S_2)$ is the edge set of a subgraph of $Vor(S)$ with the properties:

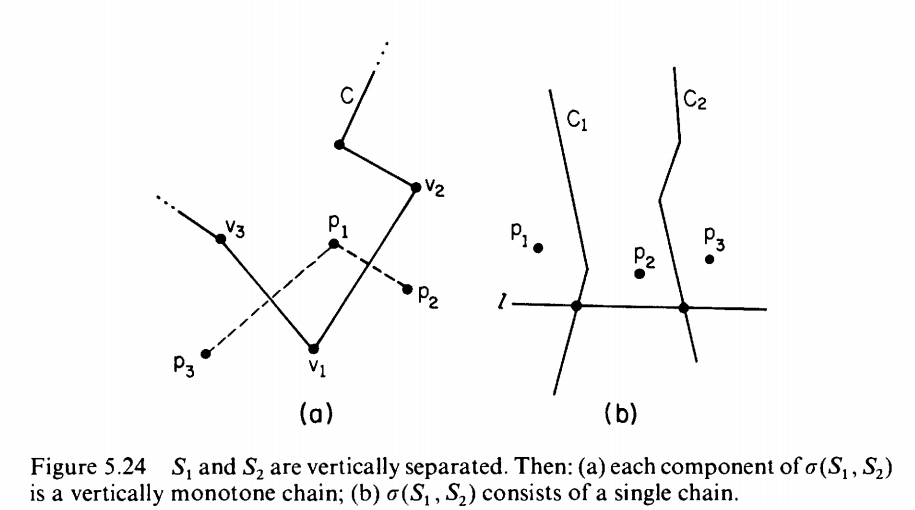

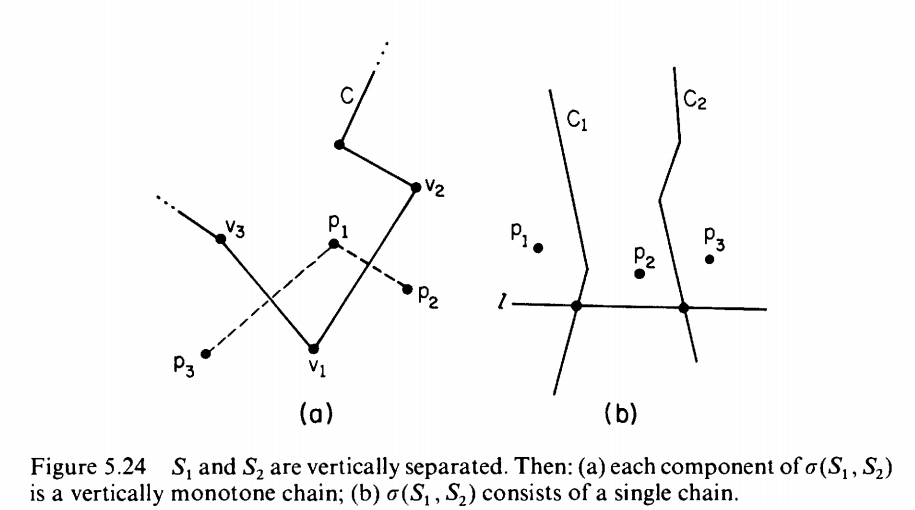

- $\delta(S_1,S_2)$ consists of edge-disjoint cycles and chains. If a chain has just one edge, this is a straight line; otherwise its two extreme edges are semi-infinite rays.

- If $S_1$ and $S_2$ are linearly separated, then, $\delta(S_1,S_2)$ consists of a single monotone chain.

Proof

- Color the polygons ${V(i):p_i\in S_1}$ in red and each of the polygons $V(j):p_j\in S_2$ in green. It is well-known that the boundaries between polygons of different colors are edge-disjoint cycles and chains. Each component of $\delta(S_1, S_2)$ partitions the plane into two parts. Thus a chain either consists of a single straight line or it has rays as initial and final edges. This establishes 01.

- Just need to prove it is a chain which is monotone and unique.

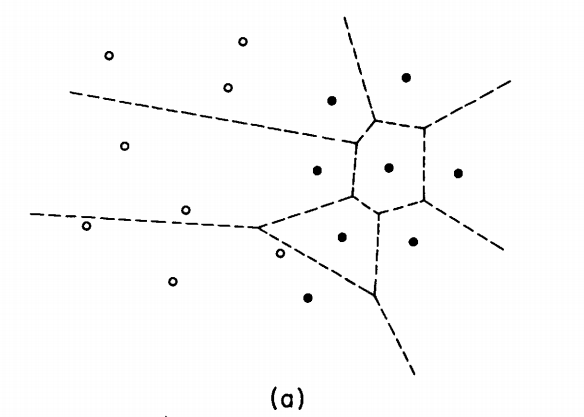

- In figure (a), by the shape of $C$, $p_2$ and $p_3$ belong to the same set, contrary to the assumption that $S_1$ and $S_2$ are separated by a vertical line. So, a vertex like $v$ is impossible and $C$ is vertically monotone. This implies that $C$ is a chain.

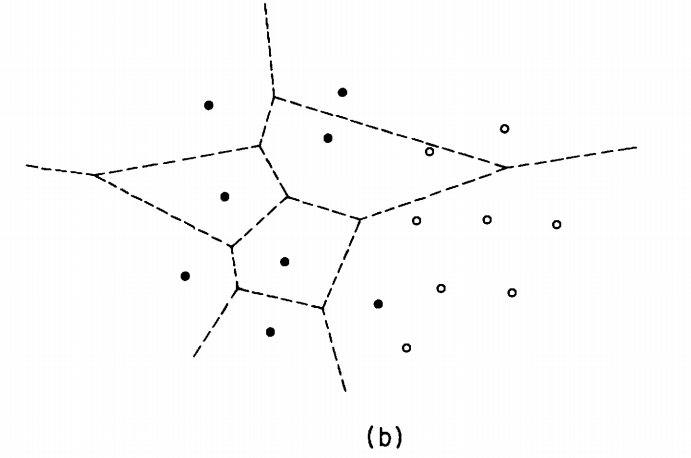

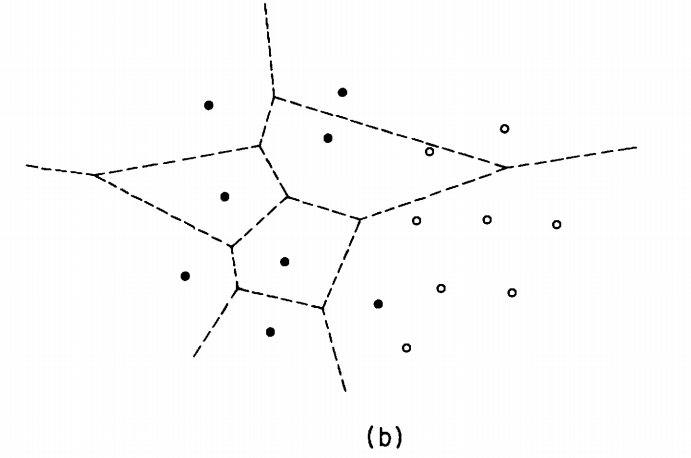

- In figure (b), $p_1$ and $p_3$ belong to the same set of the partition ${S_1,S_2}$, contradicting the hypothesis of vertical separation of these two sets. So, $\delta(S 1 , S2 )$ consists of a single monotone chain.

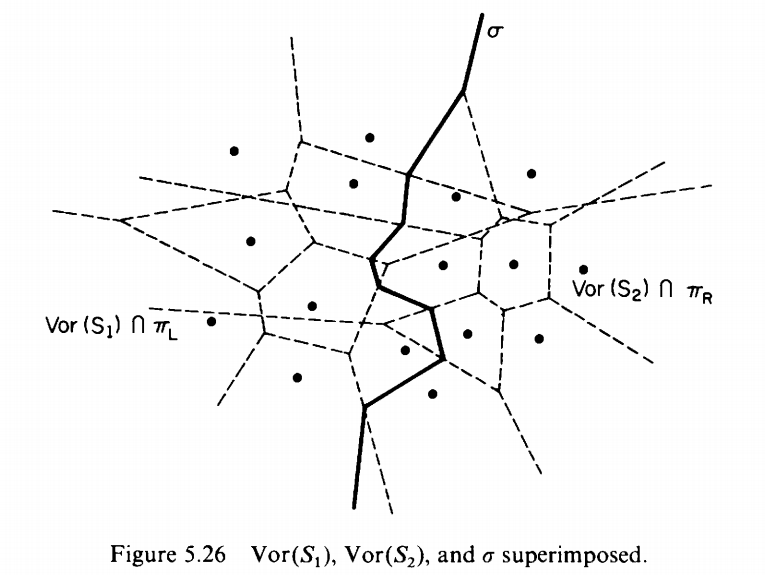

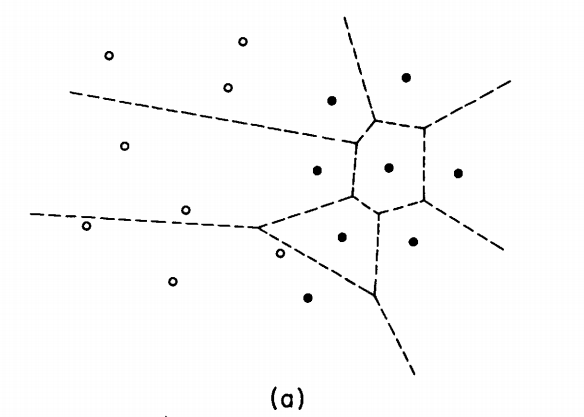

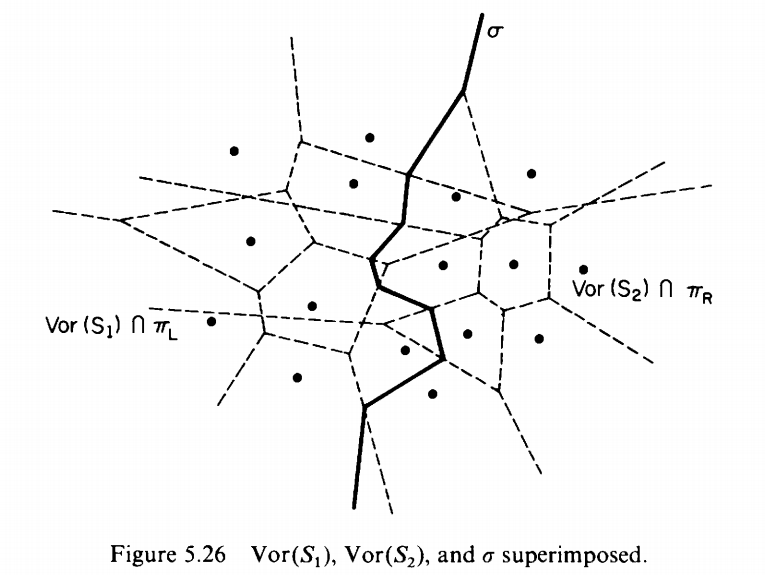

Define $\delta:=\delta(S_1,S_2)$, $\delta$ cuts the plane into a left portion $\pi_L$ and a right portion $\pi_R$.

Theorem 5.14 If $S_1$ and $S_2$ are linearly separated by a vertical line with $S_1$ to the left of $S_2$, then the Voronoi diagram $Vor(S)={Vor(S_1)\cap\pi_L}\cup{Vor(S_2)\cap\pi_R}$ .

Clearly, the success of this procedure depends on how rapidly we are able to construct $\delta$.

Constructing the Dividing Chain

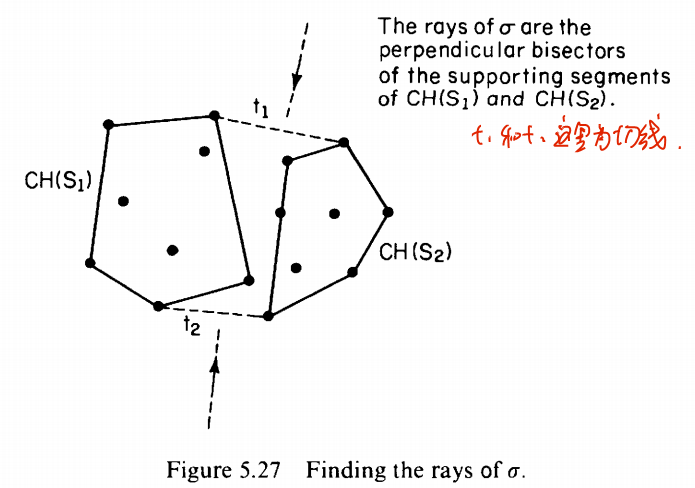

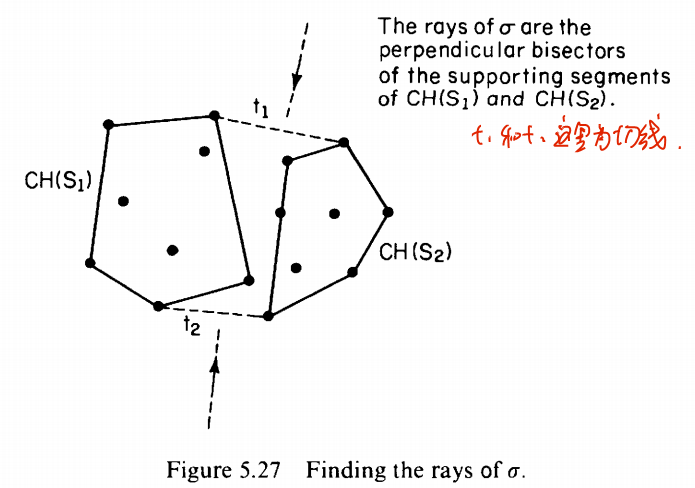

The rays (extreme edges) of $\delta$ are determined as:

The idea we find remaining segments are:

Optimization Analysis

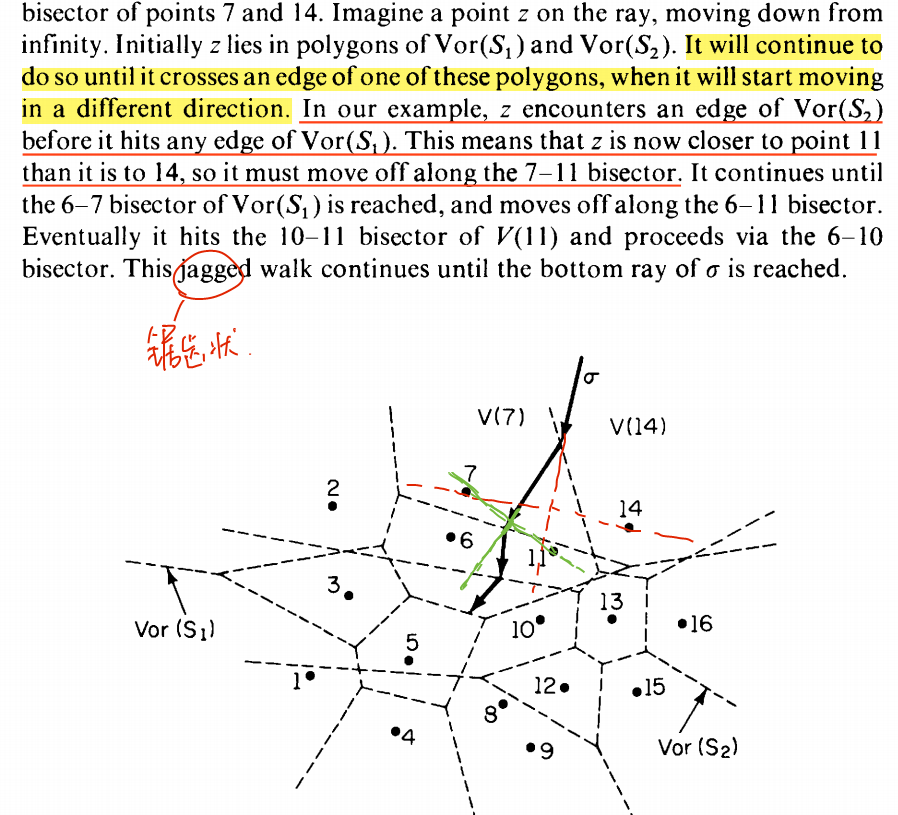

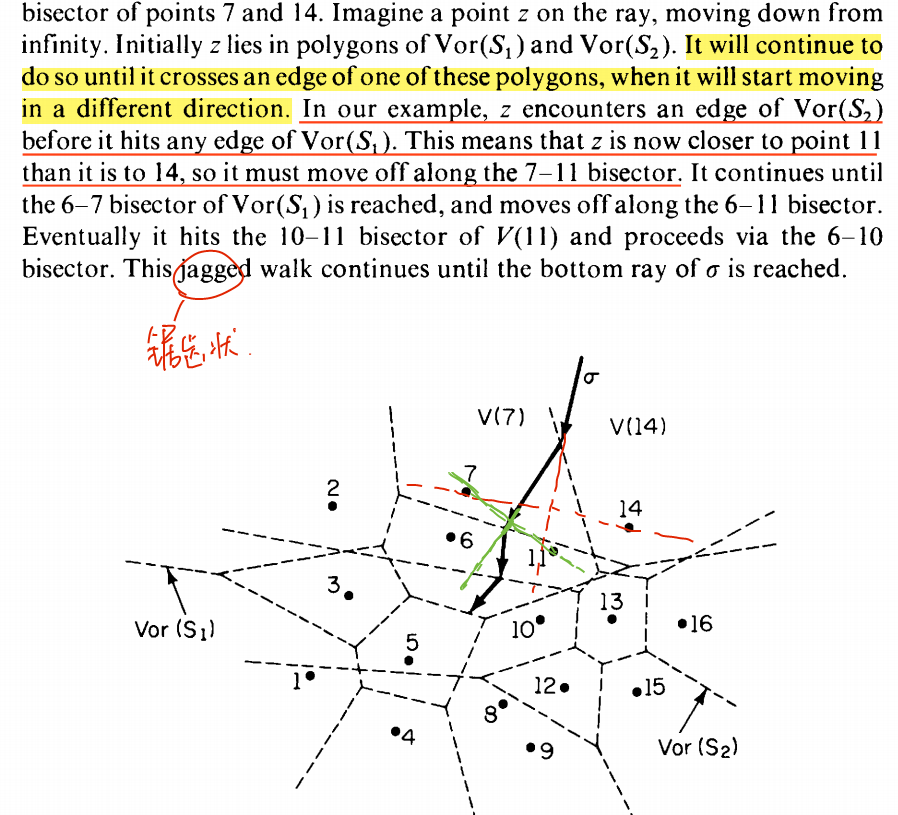

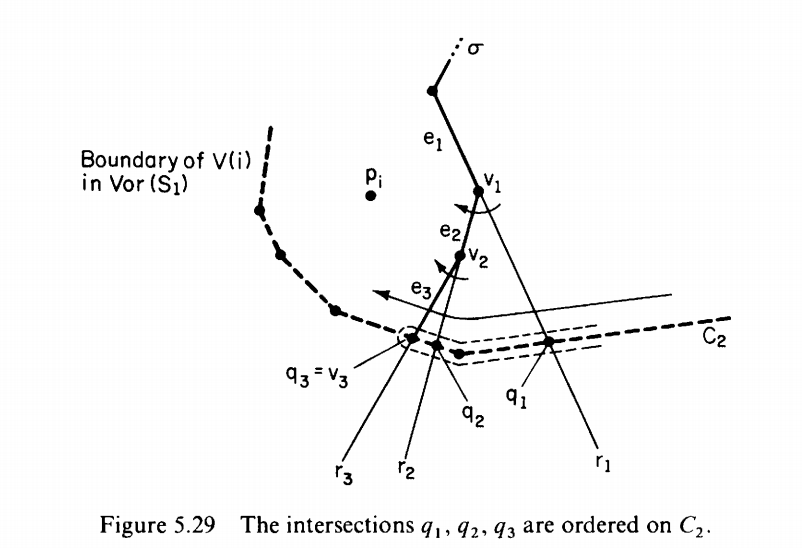

Assuming that $\delta$ is traversed in the direction of decreasing $y$, the walk obtains from the current edge $e$ and current vertex $v$, the next edge $e’$ and vertex $v’$. If $e$ separates $V(i)$ and $V(j)$, for $p_i\in S_1$ and $p_j\in S_2$, then $v’$ will be either the intersection of $e$ with the boundary of $V(i)$ in $Vor(S_1)$ or the one with boundary of $V(j)$ in $Vor(S_2)$, whichever is closer to $v$. So by scanning the boundaries of $V(i)$ in $Vor(S_1)$ and of $V(j)$ in $Vor(S_2)$ we can readily determine vertex $v’$.

Unfortunately, $\delta$ may remain inside a given polygon $V(i)$, turning many times, before crossing an edge of $V(i)$. In fact, this procedure could take as much as quadratic time.

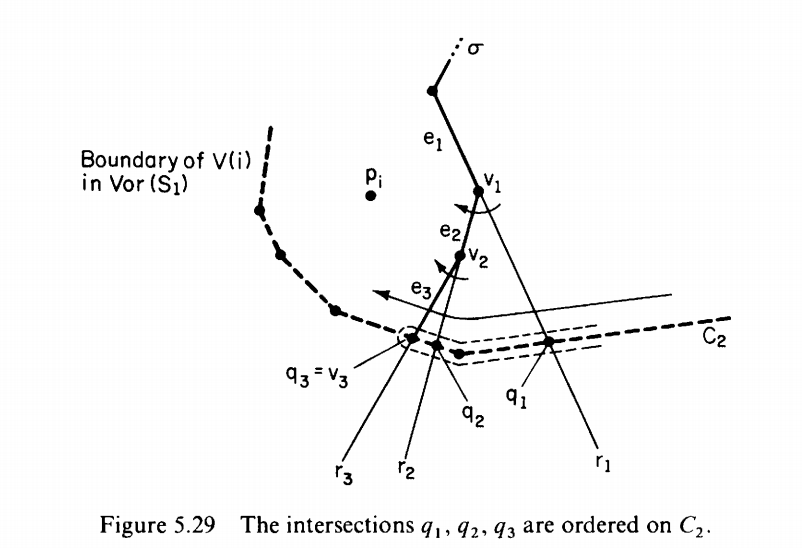

Indeed, as following figure shows, the $\delta$ would always closer to $p_i$ since it should remain the bisector between $p_i$ and other points in $Vor(S_2)$. This proves that $C_2$, i.e., the boundary of $V(i)$ in $Vor(S_1)$, needs to be scanned clockwise, with no backtrack, when determining $q_1,q_2,\cdots$. An analogous argument shows that the boundary of any $V(j)$ in $Vor(S_2)$ needs to be scanned counterclockwise, with no backtrack.

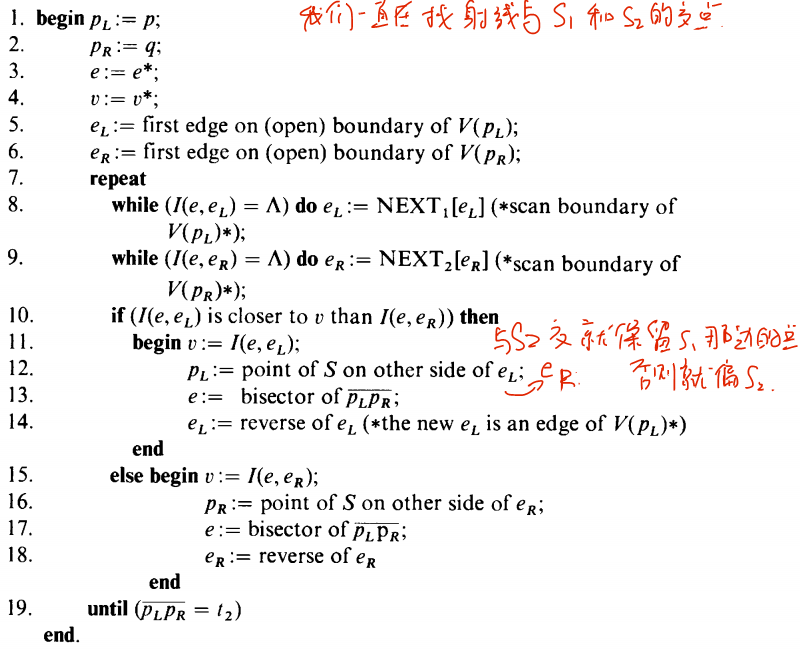

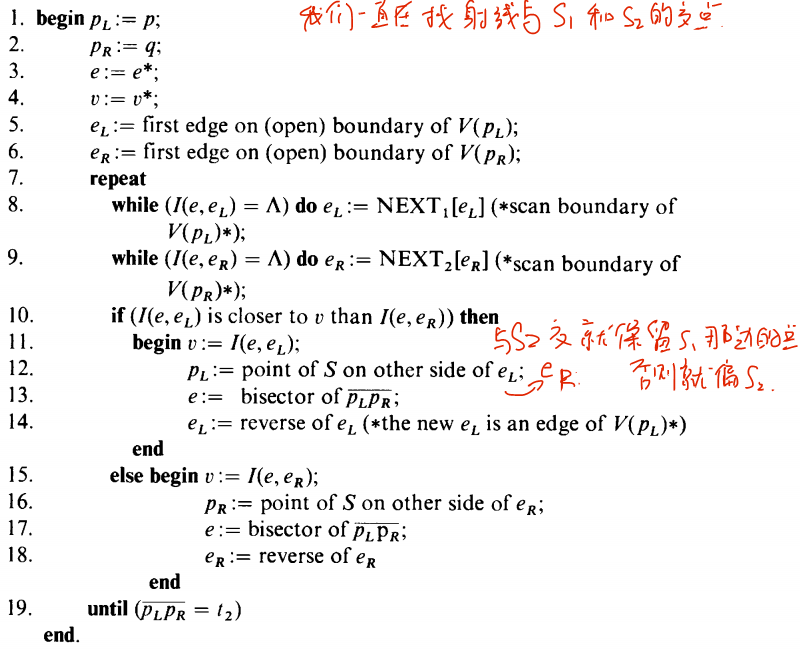

The algorithm determine $\delta$ shown as follows:

- $e^,v^$ is the start ray edge and point at infinity.

- $e_L,e_R$ are edges in $Vor(S_1),Vor(S_2)$ and $e$ is the current edge of $\delta$.

- It maintains two points of $S$, $p_L\in S_1$ and $p_R \in S_2$, so that the current edge $e$ is perpendicular bisector of $\overline{p_Lp_R}$.

- By $I(e,e’)$ we denote the intersection of edges $e$ and $e’$; $I(e,e’)=\Lambda$ means that $e$ and $e’$ do not intersect.

To find the intersection boundary, scan the polygon edge in certain direction exactly once without trace back to ensure the construction time of the chain to be linear.

Since there are no more than $3N-6$ edges in $Vor(S_1)$ and $Vor(S_2)$ together, and $O(N)$ vertices in $\delta$, then the entire construction of $\delta$ takes only linear time.

Theorem 5.15 The Voronoi diagram of a set of $N$ points in the plane can be construct in $O(N\log N)$ time, and this is optimal.

Proof

$$

T(N)=2T(N/2)+O(N)=O(N\log N)

$$

Thomas Men

$\int_{birth}^{death}\text{study} dt = \text{life}$