Point Location query Given a map and a query point $q$ specified by its coordinates, find the region of the map containing $q$. A map, of course, is nothing more than a subdivision of the plane into regions, a planar subdivision.

Idea To preprocess the maps and to store them in a data structure that makes it possible to answer point location queries fast.

Slab Method

Let $S$ be a planar subdivision with $n$ edges. The planar _ point_ _ location_ _ problem_ is to store $S$ in such a way that we can answer queries of the following type:

- Given a query point $p$, report the face $f$ of $S$ that containing $q$. If $q$ lies on an edge or coincides with a vertex, the query algorithm should return this information.

Method:

-

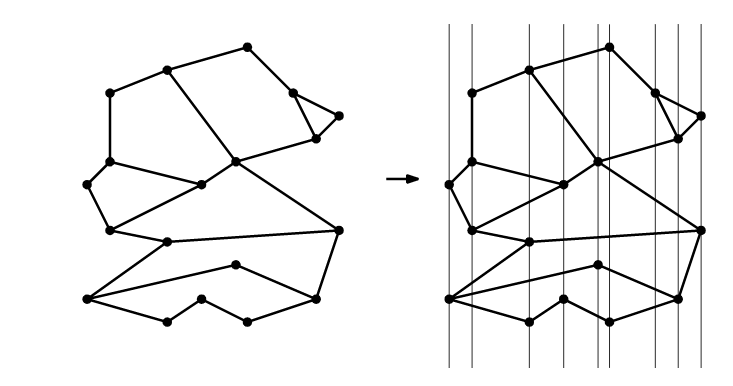

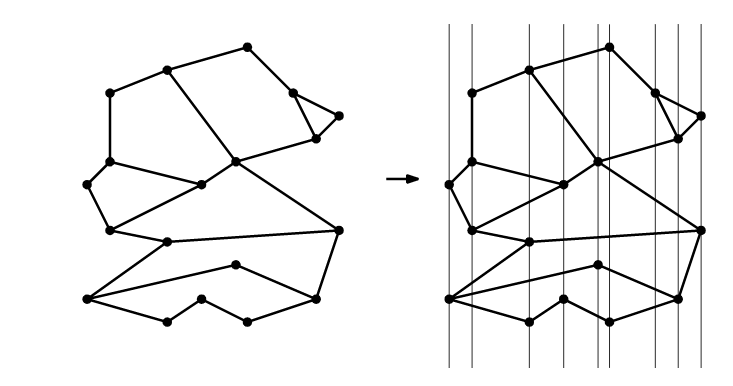

We draw vertical lines through all vertices of the subdivision. This partitions the plane into vertical slabs. We store the $x$-coordinates of the vertices in sorted order in an array. This means it possible to determine in $O(\log n)$ time the slab that contains a query point $q$. Within a slab, there are no vertices of $S$. We label each edge with the face $S$ that is immediately above it inside the slab.

The query algorithm is:

- We do a binary search with the $x$-coordinate of the query point $q$ in the array storing the $x$-coordinates of the vertices of the subdivision. This tells us the slab containing $q$.

- Do a binary search with $q$ in the array for that slab. The elementary operation in this binary search is: Given a segment $s$ and a point $q$ such that the vertical line through $q$ intersects $s$, determine whether $q$ lies above $s$, below $s$,or on $s$. This tells us the segment directly below $q$, provided there is one. The label stored with that segment is the face of $S$ containing $q$. If we find that there is no segment below $q$ then $q$ lies in the unbounded face.

The complexity:

Chain Method

The key to this method is the notion of ‘chain’ as given by the following:

Definition A chain $C=(u_1,\cdots,u_p)$ is a PSLG (planar straight-line graphs) with vertex set ${u_1,\cdots,u_p}$ and edge set ${(u_i,u_{i+1}):i=1,\cdots,p-1}$.

Definition A chain $C=(u_1,\cdots,u_p)$ is said to be monotone w.r.t a straight line $l$ if a line orthogonal to $l$ intersects $C$ in exactly one point.

The operation of deciding on which side of a $p$-vertex chain $C$ a query point $z$ lies – called discrimination of $z$ against $C$, is effected in time $O(\log p)$.

Property For any two chains $C_i$ and $C_j$ of $\mathcal{L}$, the vertices of $C_i$ which are not vertices of $C_j$ lie on the same side of $C_j$.

$\mathcal{L}$ is referred to as a monotone complete set of chains of $G$. Thus if there are $r$ chains in $\mathcal{L}$ and the longest chain has $p$-vertices, then the search uses worst-case time $O(\log p\cdot\log r)$.

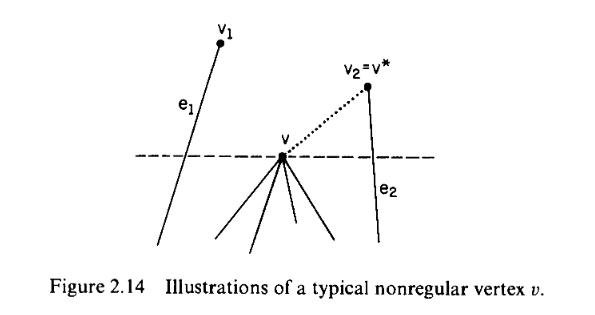

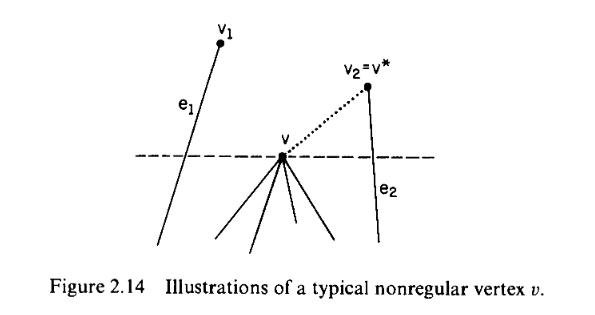

Definition Let $G$ be a PSLG with vertex set ${v_1,\cdots,v_n}$, where the vertices are indexed from right-bottom to the upper-left. A vertex $v_j$ is said to be regular if there are integers $i<j<k$ such that $(v_i,v_j)$ and $(v_j,v_k)$ are edges of $G$. Graph $G$ is said to be regular if each $v_j$ is regular for $1<j<N$ (i.e., with the exception of the two extreme vertices $v_1$ and $v_n$).

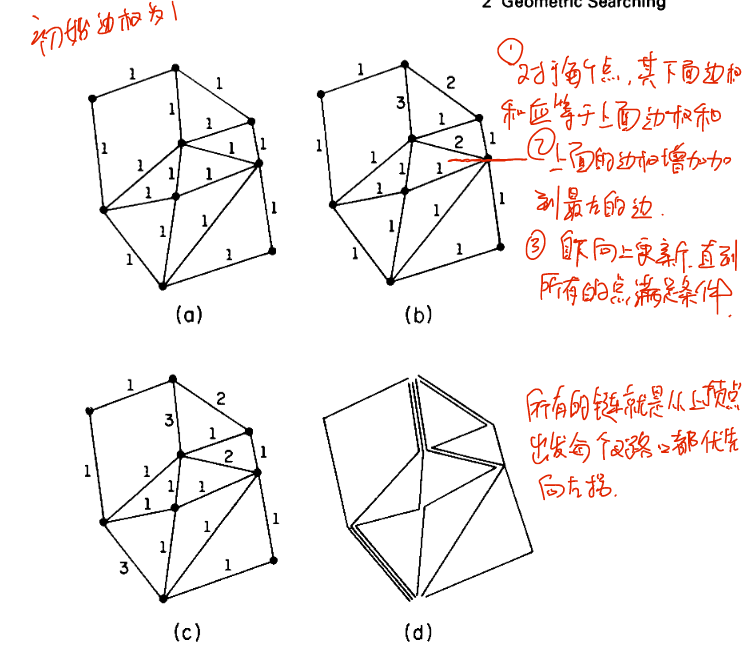

How we transform a non-regular graph into a regular one (to keep the monotone chain divide possible)? In the sweep, for each vertex $v$ reached we perform the following operation:

- locate $v$ in an interval in the status structure

- update the status structure

- if $v$ is not regular, add an edge from $v$ to the vertex associated with the interval determined in (1).

Theorem An $N$-vertex PSLG can be regularized in time $N\log N$ and space $O(N)$.

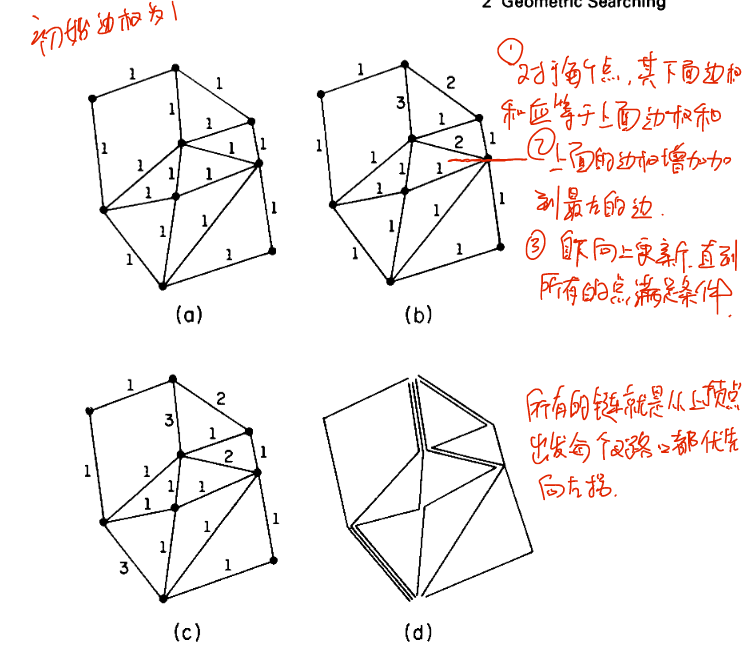

Then, we find all chains for $G$ in $O(#nodes+#edges)$, as follows:

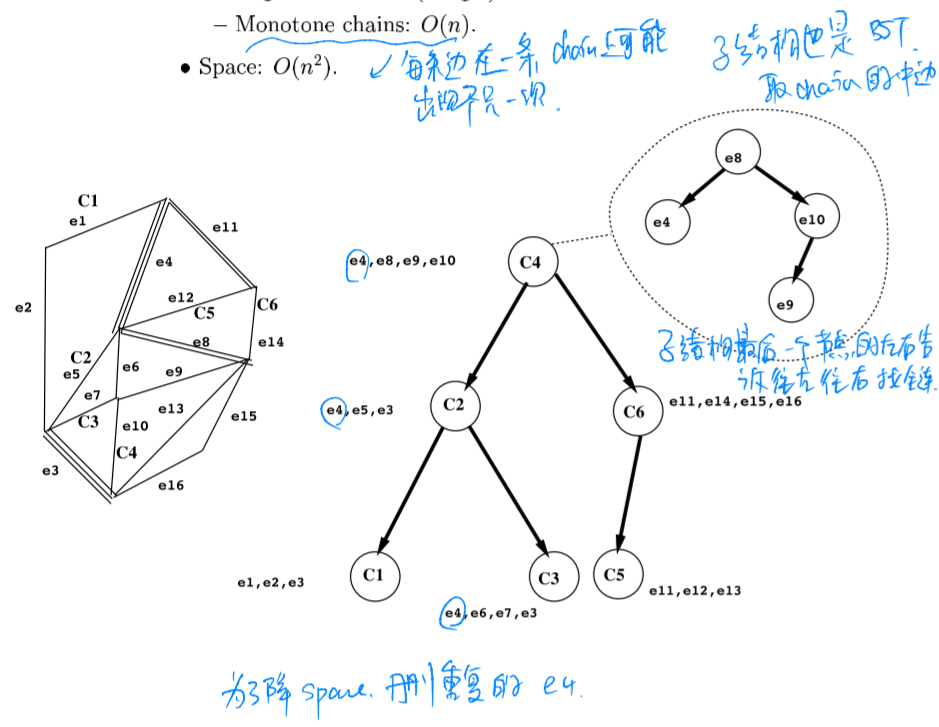

The complexity:

- Location of a point in a regularized graph with $r$ chains and $p$ nodes per chain requires $O(\log p\log r)$ time.

- There are worst regular graphs with $n/2$ chains and $n/2$ nodes per chain. Location requires then $O(\log n\log n)$ time.

- Preprocessing requires:

- Regularization: $O(n\log n)$.

- Monotone chains: $O(n)$.

- Space: $O(n^2)$.

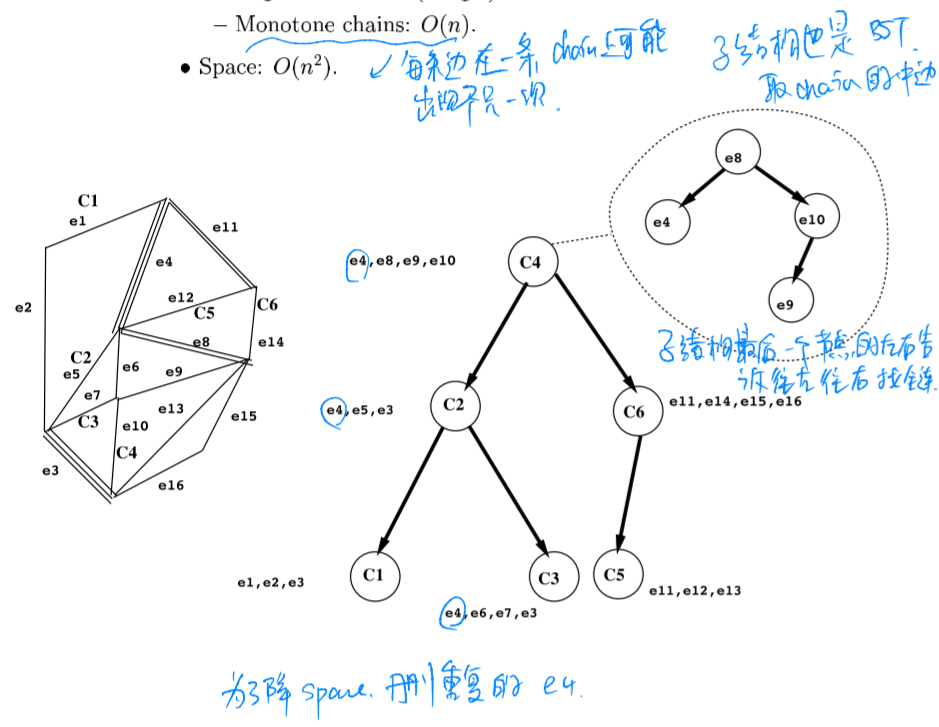

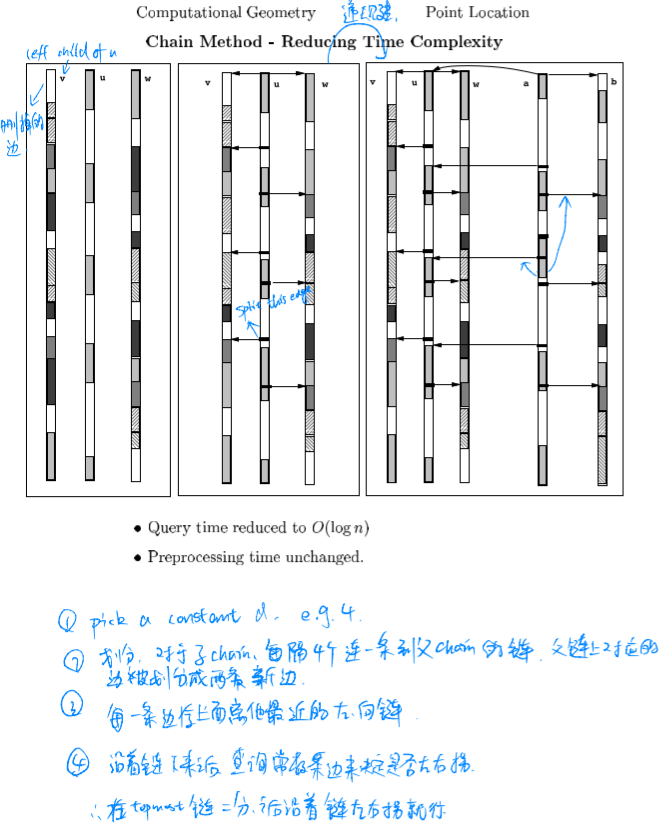

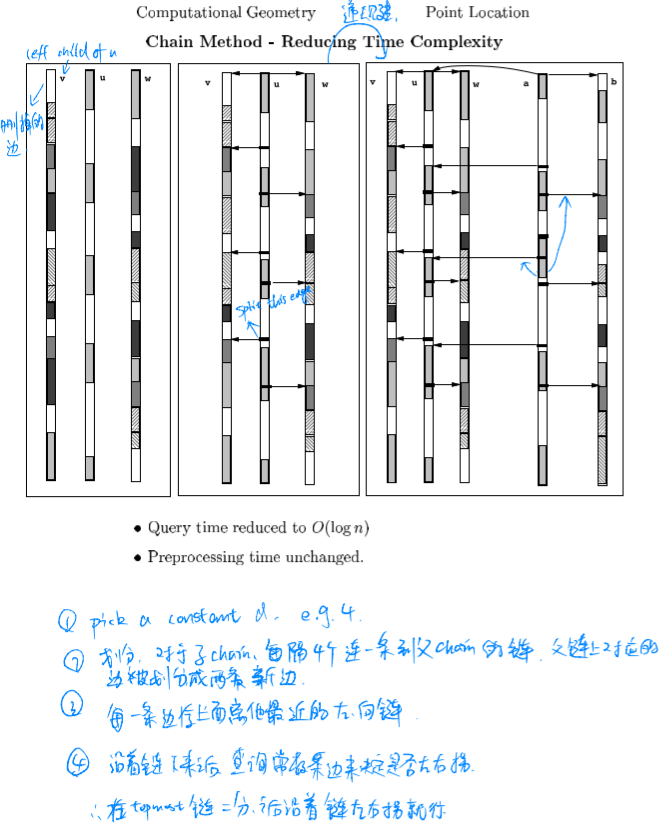

Chain Method - Reducing Space Complexity

Define:

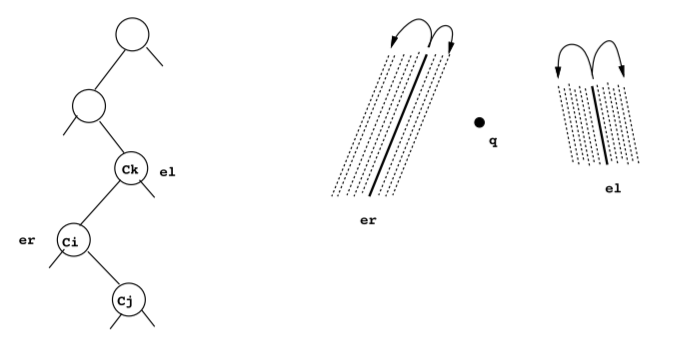

- $e_l:=$ last left-forcing edge when going down the chain tree.

- $e_r:=$ last right-forcing edge when going down the chain tree.

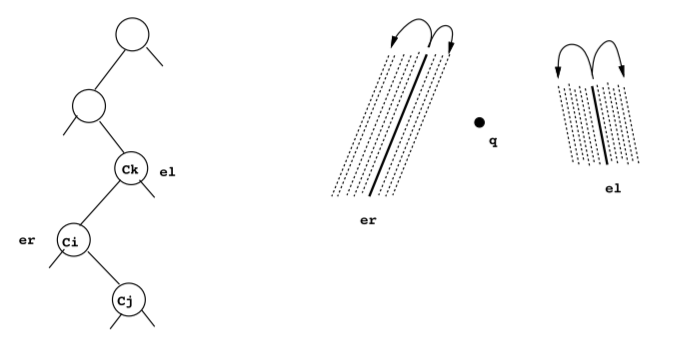

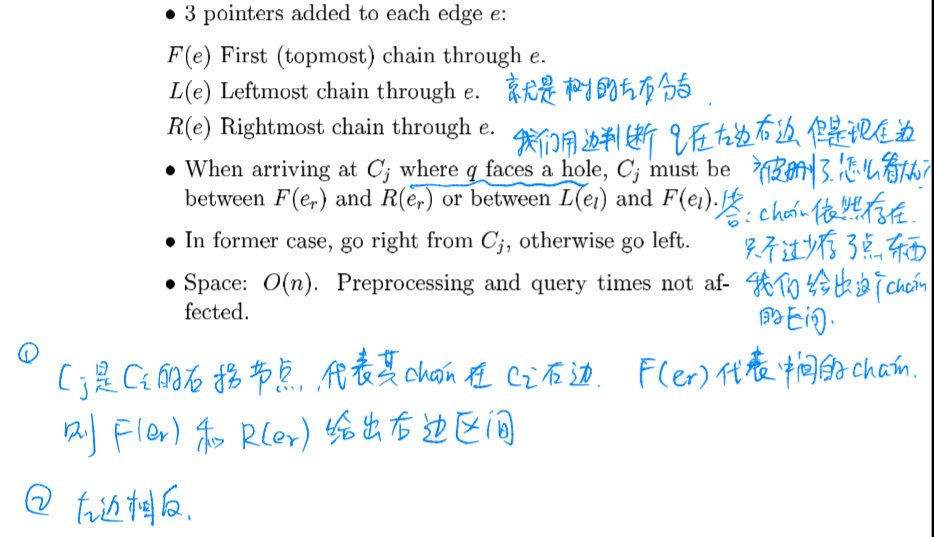

3 pointers added to the each edge $e$:

- $F(e)$ First (topmost) chain through $e$.

- $L(e)$ Leftmost chain through $e$.

- $R(e)$ Rightmost chain through $e$.

When arriving at $C_j$ where $q$ faces a hole, $C_j$ must be between $F(e_r)$ and $R(e_r)$ or between $L(e_l)$ and $F(e_l)$. In former case, go right from $C_j$, otherwise go left.

Space: $O(n)$. Preprocessing and query times not affected.

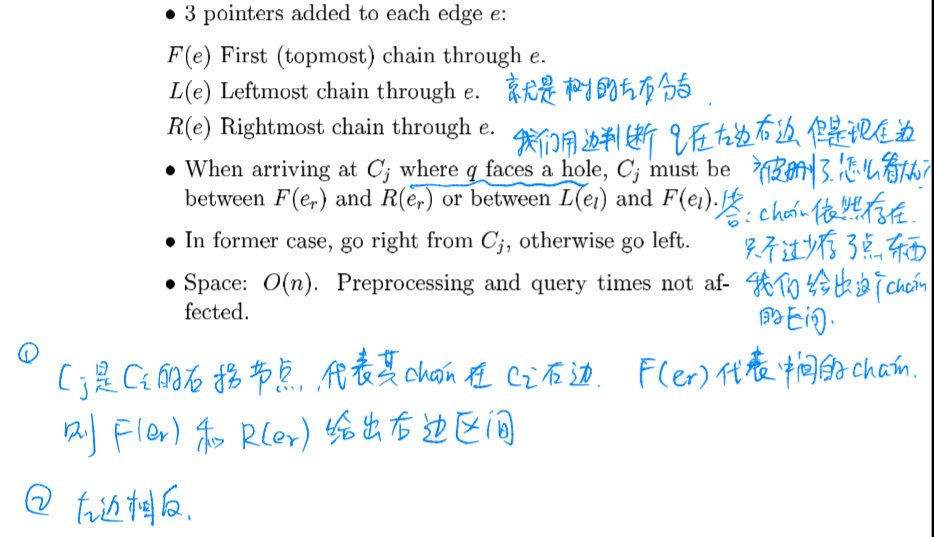

To reduce the time complexity:

$c(u)$ original number of nodes (primary structure).

$t(u)$ total number of nodes, which includes those nodes added when adding the bridges. Note that $t(u)=c(u)$ if $u$ is a leaf.

Below is the analysis:

$$

\begin{align}

t(u)&<c(u)+(t(v)+t(w))/d+2\\

\sum_{u}t(u)&<\sum_{u}c(u)+\frac{1}{d}(\sum_ut(u)-t(root))+2n\\

(1-\frac{1}{d})\sum_ut(u)&<\sum_uc(u)+2n\\

\sum_ut(u)&<\frac{d}{d-1}(\sum_uc(u)+2n)\in \mathcal{O}(n)

\end{align}

$$

where

- $d$ is every $d$ time.

- $+2$ means there are 2 topmost bridges for primary chain.

Randomized Incremental Algorithm

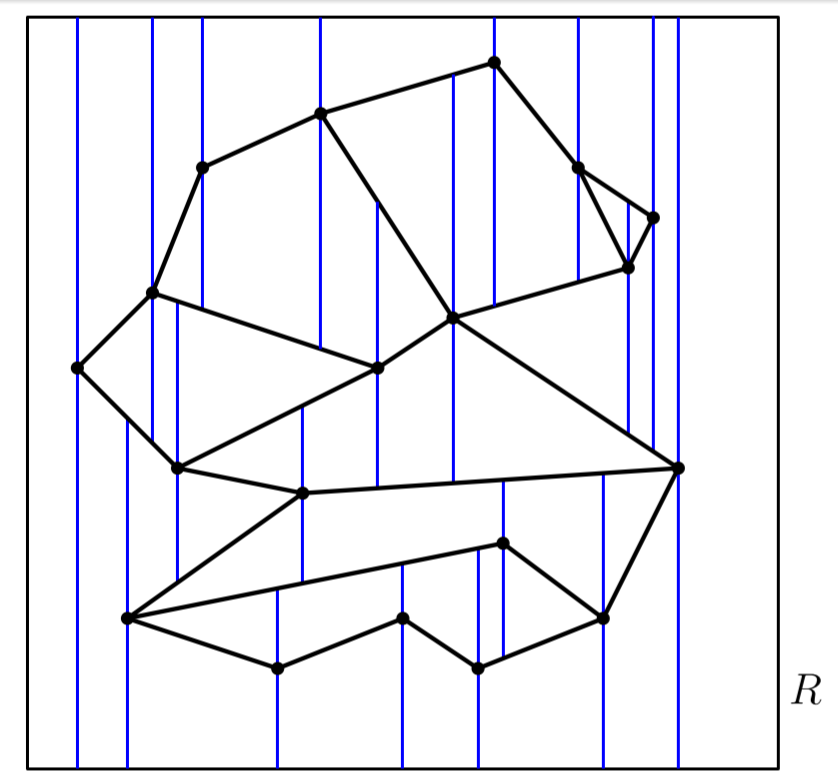

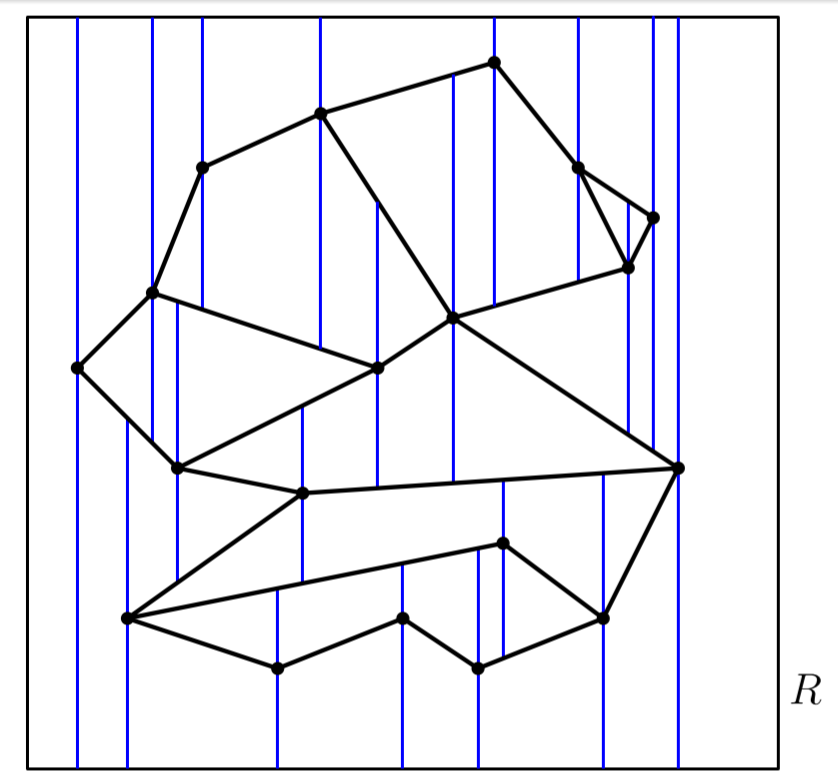

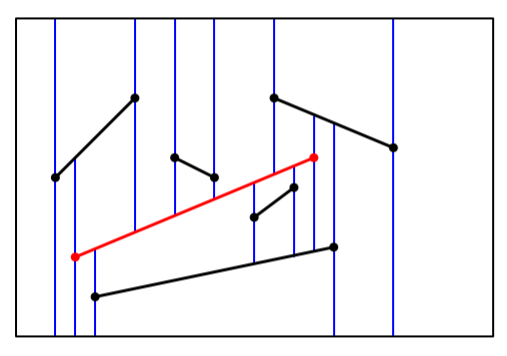

The first algorithm’s vertical strips idea gave a refinement of the original subdivision, but the number of faces went up from linear in $n$ to quadratic in $n$.

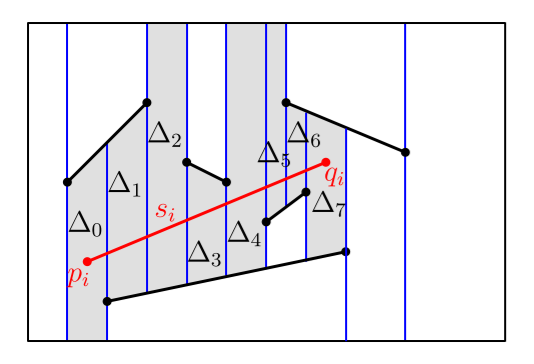

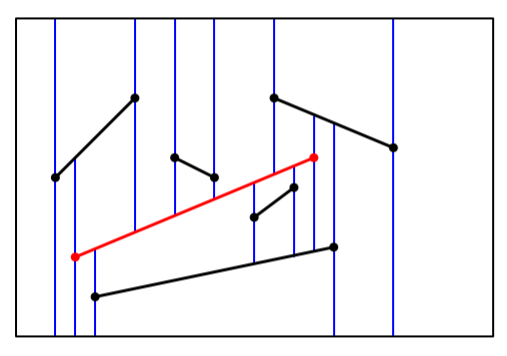

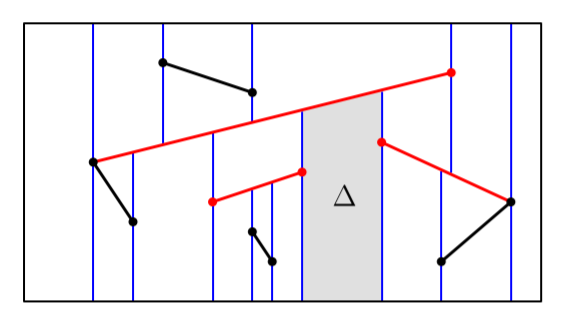

Definition Suppose we draw vertical extensions from every vertex up and down, but only until the next line segment,

- Assume the input line segments are not vertical.

- Assume every vertex has a distinct $x$-coordinate.

- Assume we have a bounding box $R$ that encloses all line segments that define the subdivision.

This is called the vertical decomposition or trapezoidal decomposition.

Every face has a vertical left and/or right side that is a vertical extension, and is bounded from above and below by some line segment of the input. The left and right sides are defined by some endpoint of a line segment.

Two trapezoids (including triangles) are neighbours if they share a vertical side. A trapezoid could have many neighbours if vertices had the same $x$-coordinate.

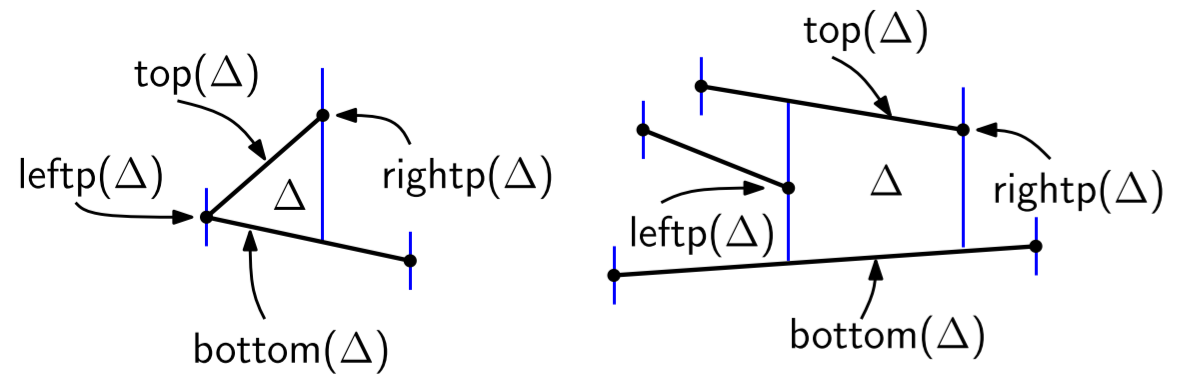

Our structure is:

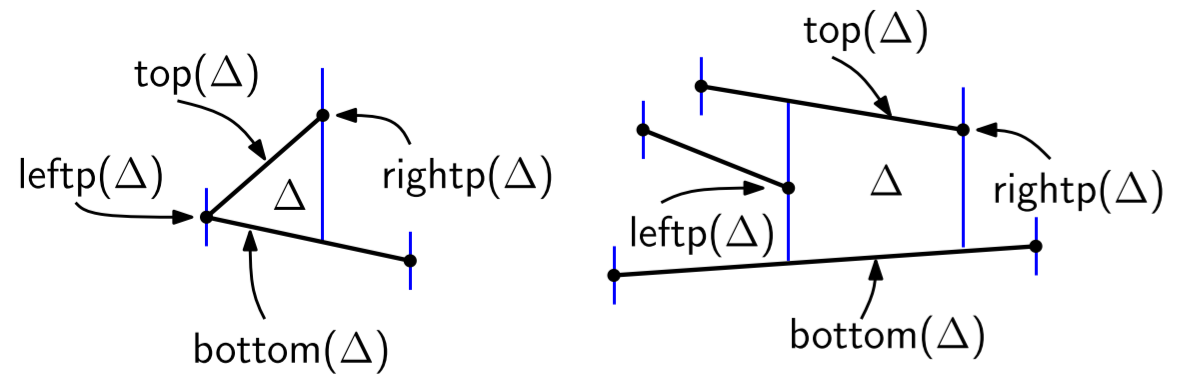

- Every face $\Delta$ is an object; it has fields for top($\Delta$), bottom($\Delta$), leftp($\Delta$), and rightp($\Delta$) (two lines segments and two vertices).

- Every face has fields to access its up to four neighbours.

- Every line segment is an object and has fields for its endpoints (vertices) and the name of the face in the original subdivision directly above it.

- Each vertex stores its coordinates.

Lemma 6.1 Each face in a trapezoidal map of a set $S$ of line segments in general position (no two distinct endpoints lie on a common vertical line) has one or two vertical sides and exactly two non-vertical sides.

Lemma 6.2 The trapezoidal map $\mathcal{T}(S)$ of a set $S$ of $n$ line segments in general position contains at most $6n+4$ vertices and at most $3n+1$ trapezoids.

Proof A vertex of $\mathcal{T}(S)$ is either:

- A vertex of $R$, where $R$ is the outer rectangular.

- An endpoint of a segment in $S$, or else

- The point where the vertical extension starting in an endpoint abuts on another segment or an the boundary of $R$. Every endpoint of a segment induces two vertical extensions – one upward and one downward. ($2n$ points and 2 lines up&down)

In total $4+2n+2(2n)=6n+4$.

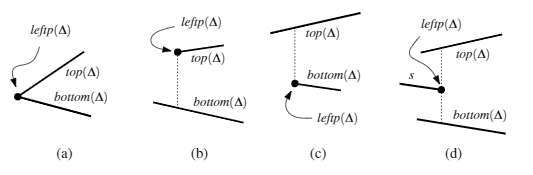

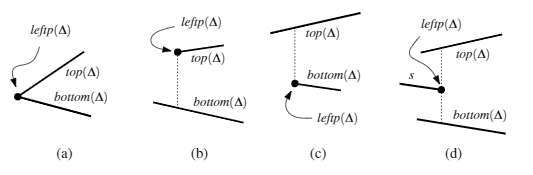

For bound of trapezoids number: here we give a direct proof, using the point leftp(∆).

- the lower left corner of $R$ plays this role for exactly one trapezoid, (1)

- a right endpoint of a segment can play this role for at most one trapezoid, ($n$)

- a left endpoint of a segment can be the leftp(∆) of at most two different trapezoids. ($2n$)

In total: $1+n+2n=3n+1$.

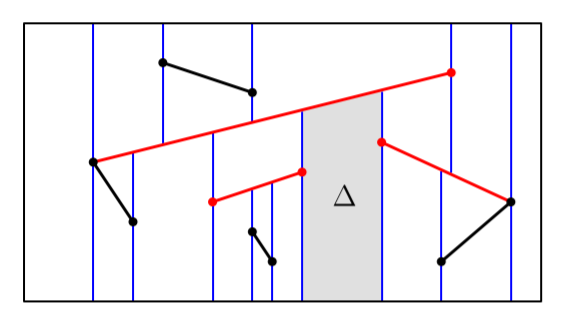

We will use randomized incremental construction to build, for a set $S$ of non-crossing line segments:

- A vertical decomposition $T$ of $S$ and $R$

- A search structure $D$ whose leaves correspond to the trapezoids of $T$

Start with $R$, then add the line segments in random order and maintain $T$ and $D$.

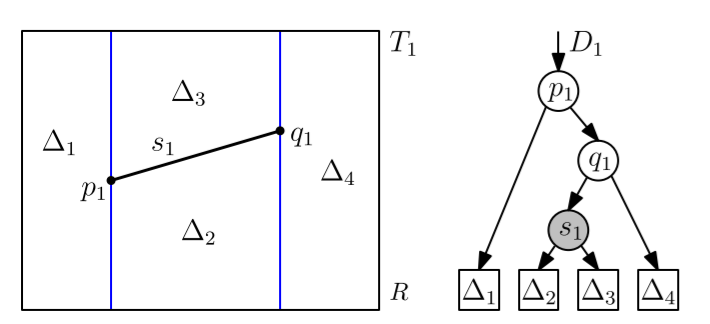

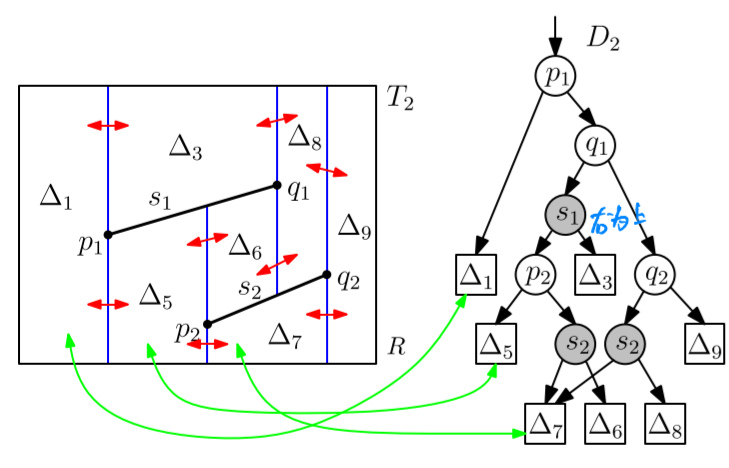

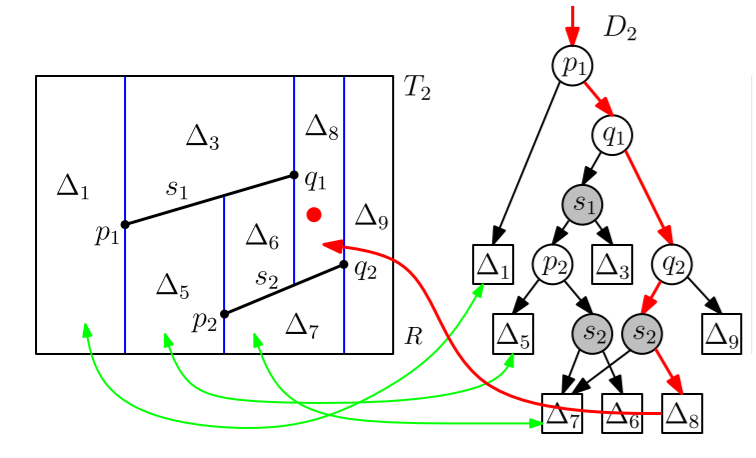

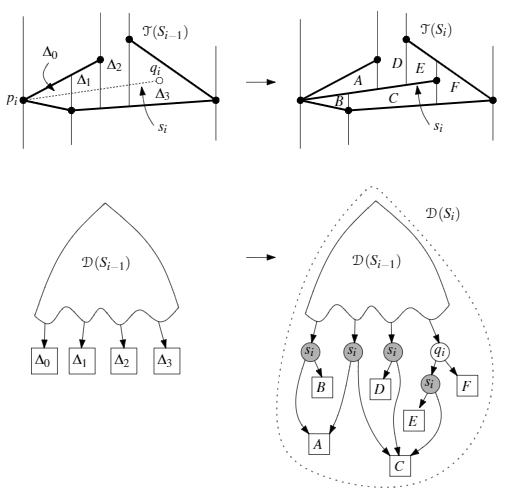

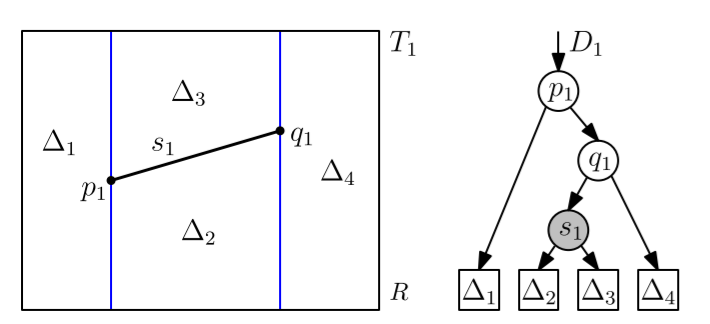

Let $s_1,\cdots, s_n$ be the $n$ line segments in random order. Let $T_i$ be the vertical decomposition of $R$ and $s_1,\cdots,s_i$, and let $D_i$ be the search structure obtained by inserting $s_1,\cdots,s_i$ in this order.

We want only one leaf in $D$ to correspond to each trapezoid; this means we get a directed acyclic graph (DAG) (one leaf could only have one father node) instead of a search tree (one father per son).

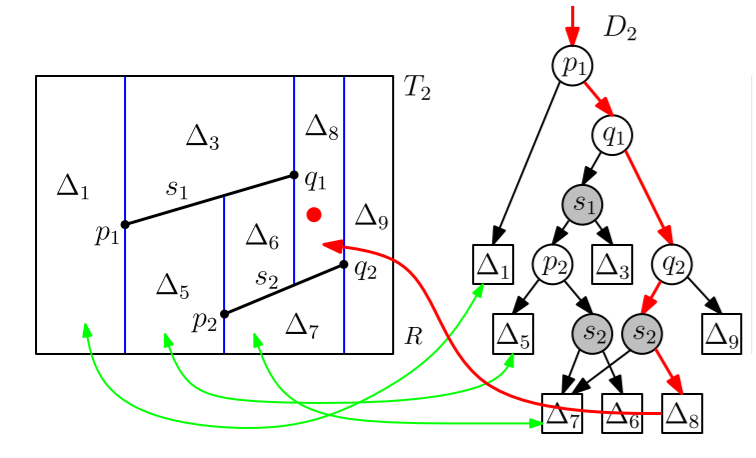

Right is the the point location query.

The incremental step:

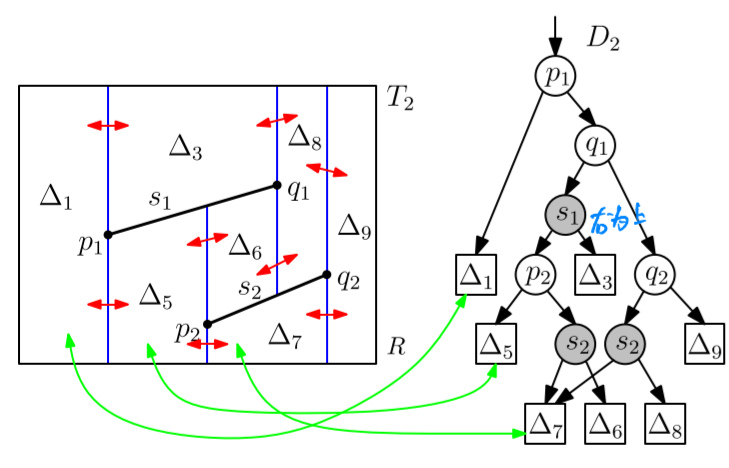

Suppose we have $D_{i-1}$ and $T_{i-1}$, how do we add $s_i$?

Because $D_{i-1}$ is a valid point location structure for $s_1,\cdots,s_{i-1}$, we can use it to find the trapezoid of $T_{i-1}$ that contains $p_i$, the left endpoint of $s_i$ (query process). Then we use $T_{i-1}$ to find all other trapezoids that intersect $s_i$, because every face stores the information of its neighbour.

After locating the trapezoid that contains $p_i$, we can determine all $k$ trapezoids that intersect $s_i$ in $O(k)$ time by traversing $T_{i-1}$. The update of the vertical decomposition can be finished in $O(k)$ as well. More specifically:

-

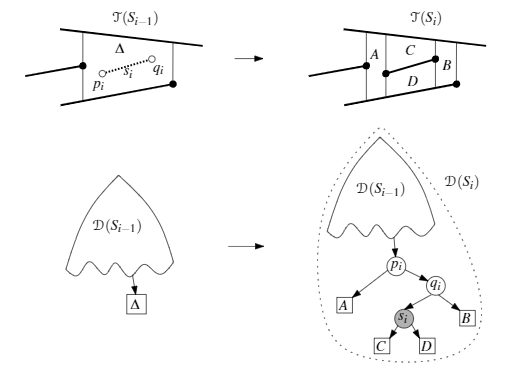

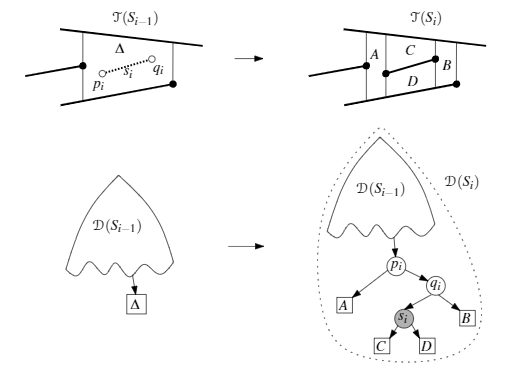

If line segment $s_i$ is completely contained in a trapezoid $\Delta=\Delta_0$, then we can update as follows:

-

To update $T$, we delete ∆ from $T$, and replace it by four new trapezoids $A,B,C,$ and $D$.

-

To update $D$, what we must do is replace the leaf for $\Delta$ by a little tree with four leaves.

-

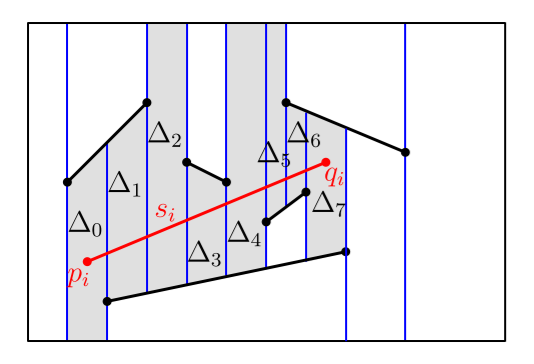

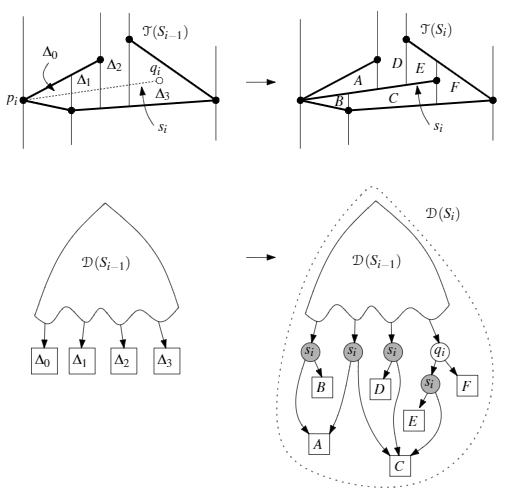

If $s_i$ intersects $k_i$ trapezoid:

- To update $T$, we first erect vertical extensions through the endpoints of $s_i$ and re-index them, $O(k_i)$.

- To update $D$, If $\Delta_0$ has the left endpoint of $s_i$ in its interior (which means it has been partitioned into three new trapezoids) then were place the leaf for $\Delta_0$ with an $x$-node for the left endpoint of $s_i$ and a $y$-node for the segment $s_i$. Similarly, if $\Delta_k$ has the right endpoint of $s_i$ in its interior, were place the leaf for $\Delta_k$ with an $x$-node for the right endpoint of $s_i$ and a $y$-node for $s_i$. Finally, the leaves of $\Delta_1$ to $\Delta_{k-1}$are replaced with single $y$-nodes for the segment $s_i$. (Update by replacing $k_i$ leaves by $O(k_i)$ new internal nodes and $O(k_i)$ new leaves.)

- The maximum depth increase is three nodes.

Space and Time analysis

For any trapezoid $\Delta$, there are at most $4$ line segments whose insertion would have created it (top($\Delta$), bottom($\Delta$), leftp($\Delta$), rightp($\Delta$)).

Space

Let $n_i$ be # of “new” trapezoids of $T_i$, i.e., the ones that are not trapezoids of $T_{i-1}$. Then we have:

$$

|D_i|-|D_{i-1}|=O(n_i)

$$

Here we have $n_i=\Theta(k_i)$, where $k_i$ is the # of trapezoids of $T_{i-1}$ intersected by $s_i$.

$T_i$ has $\leq 3i+1$ trapezoids and when we add line $s_i$, each trapezoid has probability $\leq 4/i$ of being new, where $i$ is remaining # of line segments. Hence,

$$

\mathbb{E}[n_i]\leq(3i+1)\cdot4/i\leq 13

$$

Therefore,

$$

\mathbb{E}[|D_n|]=\mathbb{E}[O(\sum_{i=1}^n n_i)]=O(\sum_{i=1}^n\mathbb{E}[n_i])=O(13n)=O(n)

$$

Query Time

Define $X_i=1$ if the search path for any query point $p$ increases in iteration $i$. Otherwise, $X_i=0$. In other words, $X_i=1$ if and only if trapezoid containing $p$ in $T_i$ is new.

$$

\mathbb{E}[\sum_{i=1}^nX_i]=\sum_{i=1}^n\mathbb{E}[X_i]=\sum_{i=1}^n\mathbb{P}[X_i=1]

$$

Hence, $P[X_i=1]\leq 4/i$, since at most $4$ of the $i$ segments in $T_i$ could have caused the trapezoid containing $p$ to be new (just created).

$$

\mathbb{E}[\sum_{i=1}^nX_i]=\sum_{i=1}^n\mathbb{P}[X_i=1]\leq\sum_{i=1}^n 4/i=O(\log n)

$$

The search path increases by at most $3$ at a time, so the final search is $O(\log n)$.

Theorem Given a planar subdivision defined by a set of $n$ non-crossing line segments in the plane, we can preprocess it for planar point location queries in $O(n\log n)$ expected time, the structure uses $O(n)$ expected storage, and the expected query time is $O(\log n)$.

Thomas Men

$\int_{birth}^{death}\text{study} dt = \text{life}$